Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To describe the use of coxibs outside of licensed indications and recommended dosing ranges including rofecoxib 50 mg, valdecoxib 20 to 40 mg, and celecoxib 400 mg.

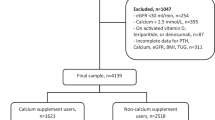

DESIGN: Cross-sectional study of coxib utilization in 2002 and 2003 and retrospective cohort analysis of new users.

PARTICIPANTS: Patients with known age and sex enrolled in Tennessee’s Medicaid program.

MEASUREMENTS: The prevalence of coxib use by dose and duration, and the proportion of persons initially prescribed a high-dose coxib and indications for such use.

RESULTS: The estimated daily prevalence of nonaspirin prescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) was 8.7% in 2002 to 2003 (45.7% coxibs). NSAID use peaked at age 65 to 74 with a prevalence of 19.8% (56.3% coxibs). Doses above the recommended daily dose for osteoarthritis accounted for 33.2% (95% confidence intervals [CIs] 32.4%, 33.9%) of celecoxib use, 14.9% (95% CI 14.4%, 15.5%) of rofecoxib use, and 52.2% (95% CI 50.6%, 53.8%) of valdecoxib use. Most of these prescriptions were for a month’s supply. For new coxib users, 13.5% were given a month’s supply for the highest dose category, and 28% refilled their prescriptions within 7 days of the end of the original prescription. Of these new chronic high-dose users, 17.2% had ischemic heart disease and 7.1% had heart failure.

CONCLUSIONS: A substantial portion of coxib prescriptions were for a month’s supply at doses above those recommended for most chronic indications. New users were also prescribed high doses despite evidence for cardiovascular comorbidity. These prescribing patterns at doses outside licensed indications are both inappropriate and potentially dangerous.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Cardiovascular Safety Review Rofecoxib. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/01/briefing/3677b2_06_cardio.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2004.

Merck. Press Release: Merck Announces Voluntary WorldWide Withdrawal of Vioxx. Merck and Co. Available at: http://www.merck.com/. Accessed September 30, 2004.

Solomon DH, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, et al. Relationship between selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and acute myocardial infarction in older adults. Circulation. 2004;109:2068–73.

Ray WA, Stein CM, Daugherty JR, Hall K, Arbogast PG, Griffin MR. COX-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of serious coronary heart disease. Lancet. 2002;360:1071–3.

Ray WA, MacDonald TM, Solomon DH, Graham DJ, Avorn J. COX-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cardiovascular disease. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety. 2003;12:67–70.

Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, et al. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1520–8.

Solomon S, McMurray JJV, Pfeffer MA, et al. Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention. N Engl J Med. Available at: http://content.nejm.org/early_release/index.shtml#2-15. Accessed February 16, 2005.

Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med. Available at: http://content.nejm.org/early_release/index.shtml#2-15. Accessed February 16, 2005.

Nussmeier NA, Whelton AA, Brown MT, et al. Complications of the COX-2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. Available at: http://content.nejm.org/early_release/index.shtml#2-15. Accessed February 16, 2005.

Review of NDA #21-042 VIOXX™ (Rofecoxxib) Merck Research Laboratories. Gaithersburg, MD: Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Arthritis Advisory Committee, Department of Health and Human Services; 1999. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/99/transcpt/3508t1.rtf. Accessed October 14, 2004.

Simon LS, Weaver AL, Graham DY, et al. Anti-inflammatory and upper gastrointestinal effects of celecoxib in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282:1921–8.

Schnitzer TJ, Truitt K, Fleischmann R, et al. The safety profile, tolerability, and effective dose range of rofecoxib in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Phase II Rofecoxib Rheumatoid Arthritis Study Group. Clin Ther. 1999;21:1688–702.

Griffin MR, Stein CM, Graham DJ, Daugherty JR, Arbogast PG, Ray WA. High frequency of use of rofecoxib at greater than recommended doses: cause for concern. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety. 2004;13:339–43.

Ott E, Nussmeier NA, Duke PC, et al. Efficacy and safety of the cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. Jun 2003;125:1481–92.

Mukherjee D, Nissen SE, Topol EJ. Risk of cardiovascular events associated with selective COX-2 inhibitors. JAMA. 2001;286:954–9.

FDA Advisory Committee Briefing Document NDA 21-042, s007 VIOXX Gastrointestinal Safety, Food and Drug Administration; February 8, 2001. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/01/briefing/3677b2_03_med.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2004.

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. Washington, DC: Public Health Service, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1988.

Physicians Desk Reference. 57th ed. Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare; 2003.

Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–13.

Griffin MR, Ray WA, Schaffner W. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and death from peptic ulcer in elderly persons. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:359–63.

Federspiel CF, Ray WA, Schaffner W. Medicaid records as a valid data source: the Tennessee experience. Med Care. 1976;14:166–72.

Zhao SZ, Burke TA, Whelton A, von Allmen H, Henderson SC. Comparison of the baseline cardiovascular risk profile among hypertensive patients prescribed COX-2-specific inhibitors or nonspecific NSAIDs: data from real-life practice. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8(suppl):S392–400.

Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:709–17.

Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–33.

Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, et al. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA. 1998;280:605–13.

Fitzgerald GA. Coxibs and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1709–11.

Topol EJ. Failing the public health—rofecoxib, Merck, and the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1707–9.

Celebrex Capsules (Celecoxib) NDA 20-998/S-009 Medical Officer Review. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Arthritis Advisory Committee, Department of Health and Human Services. Dec 1, 1998. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/adcomm/98/celebrex.htm. Accessed October 14, 2004.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

All authors received grants from Pfizer (MRG) to perform this study. Dr. Griffin is a consultant for Merck, Inc.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Roumie, C.L., Arbogast, P.G., Mitchel, E.F. et al. Prescriptions for chronic high-dose cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors are often inappropriate and potentially dangerous. J GEN INTERN MED 20, 879–883 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0173.x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0173.x